Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Life and Knowledge-Good and Bad

Some immediate questions that come to mind:

1. What is the distinction between the etz hadaat and the etz hachaim? Alternatively, what's so bad about knowledge?

2. They got thrown out of the garden, and punished with the hardships of life, simply because they ate from the wrong tree. I understand that there was a lack of obeying God here, but come on...it's a little harsh.

3. What's the connection between putting Adam in the garden, and realizing that "it's not good for man to be alone?" What about the garden made God realize that? The two stories are clearly related, as they are written intertwined with one another.

4. Why do we have to know that they were naked, and the shame (or lack thereof) that came along with it? Is that the "knowledge"? What's so important about that? (see question 1)

5. What's the role of the etz hachaim? Look at verse 9 and verses 16-17 (I posted them below). Is it a comparison of good vs. bad? How come etz hachaim is not mentioned in v. 16?

There are many more questions that come to mind, but they are not pertinent to this post, so I left them out.

I think that there's an important element that's often skipped over.

ט וַיַּצְמַח יְהוָה אֱלֹהִים מִן-הָאֲדָמָה כָּל-עֵץ נֶחְמָד לְמַרְאֶה וְטוֹב לְמַאֲכָל וְעֵץ הַחַיִּים בְּתוֹךְ הַגָּן וְעֵץ הַדַּעַת טוֹב וָרָע

and a few verses later:

טז וַיְצַו יְהוָה אֱלֹהִים, עַל-הָאָדָם לֵאמֹר: מִכֹּל עֵץ-הַגָּן, אָכֹל תֹּאכֵל.יז וּמֵעֵץ הַדַּעַת טוֹב וָרָע--לֹא תֹאכַל מִמֶּנּוּ: כִּי בְּיוֹם אֲכָלְךָ מִמֶּנּוּ--מוֹת תָּמוּת. יח וַיֹּאמֶר יְהוָה אֱלֹהִים, לֹא-טוֹב הֱיוֹת הָאָדָם לְבַדּוֹ; אֶעֱשֶׂה-לּוֹ עֵזֶר כְּנֶגְדּוֹ

The creation of Chava comes directly after the commandment of which tree to eat from. Then later, in chapter 3, the element of nakedness comes into play. Clearly, this story has a lot of sexual elements in it. It's a fairly accepted principle that the first creation story (in chapter 1) is the creation of nature. It includes plants, animals, constellations, and people. The second creation story (what we are looking at, in chapter 2) re-tells the creation of man, but the focal point is the etiology of marriage. The climax is the creation of woman, and the advise for a man to leave his parents and cleave to his wife.

So what does the beginning of the chapter have to do with marriage? Why need to know all the information about the trees and the garden?

I think the key word here is daat-knowledge. That's what the whole Gan-Eden story is focused on. That's the tree that Adam can't eat from.

It's a well known fact that "knowledge" has two definitions in Tanakh. The first is simply having an internal awareness of facts. The second, a more sexual meaning. To biblically know someone is to have sexual relations with them, as in chapter 4:

א וְהָאָדָם יָדַע אֶת-חַוָּה אִשְׁתּוֹ; וַתַּהַר וַתֵּלֶד אֶת-קַיִן

Perhaps thats what the etz hadaat is referring to. The etz hadaat and the etz hachaim are metaphors for types of sexual relations: procreation vs. an intimate knowledge of one another. And verse 9 tells the preferred type: He created a tree of life and a tree of knowledge, good and bad. The "tree of life" is good, and the "tree of knowledge" is bad. Alternatively, the good and bad can be applied both to the tree of knowledge. The "tree of knowledge" or, sex for enjoyment, is both good and bad. If the SOLE purpose of the sex is for the physical enjoyment, that's "bad". If, however, it's combined with marriage/procreation, the physical enjoyment is "good".

Verses 16 and 17 are still troublesome. Perhaps it's another rule of sex. "From every tree of the garden (types of women?) you can eat, but make sure it's not only for the enjoyment of the act."

So, according to this read, the chapter goes something like this:

-God creates Man

-God creates sex

-God gives Man rules of sex: Don't do it simply for the enjoment of sex.

-God creates Woman.

-God gives man and woman Marriage.

-The desire is too much for Woman to overcome, so she convinces Man to have sex with her, for the enjoyment of it.

-Man and Woman realize they are naked, and are embarrassed.

-Woman is punished by having childbirth be difficult.

It makes a lot of sense, and things connect better than in the "simple" read of the pesukim, although there seem to be a few flaws in the idea. First, what about the worry of God that "now man will be like one of us?" (3:5, 3:22). Where does that fit in? Also, the punishments of the snake and of Adam don't seem to have anything to do with sex or marriage.

I'm not sure that I like this read of the chapters, and it DEFINATELY wouldn't fly in (most) feminist circles, but its something different. It requires a lot more thought, but I just wanted to put the idea out there.

Tuesday, November 06, 2007

The Evolving Organization of My Bookshelf, and Me

When I first started college, I was determined to keep my room organized. I had a knack for losing things, misplacing important papers, and I inevitably took five minutes to leave because I couldn’t find my keys.

I decided that college would be my chance for a fresh start. I sorted the clothes in my closet by color, length, and style. I assigned specific drawers for my makeup, hair clips, and accessories. I made a vow never to leave my room with the bed unmade. And most importantly, I was going to keep the books on my book shelf in a logical order.

And here is where the problem started. What’s a “logical” order? There could be so many ways to arrange them. I started out putting them in size order. The big, hard cover textbooks were on the end, and the smaller, thinner books towards the middle. But this didn’t work for me. There was no reason in my mind why my (large, hardcover) siddur was next to my accounting book. So I separated the books differently. I split the book shelf into two sides, with my box of markers, pens, and pencils in the middle as the divider. To the left were the seforim I had brought with me from home, and on the right were the books I needed for class.

As time went on, the books eventually lost their places on the shelf. I would take one out and then put it back in a different spot. Two books would switch places, and then four, and then eight, until it was impossible to tell that there was ever any sort of order to the shelf. I decided it was time to reorganize the shelf.

At this point,I'd like to point out that I am majoring in Judaic Studies at the

When I started college, it was easy to divide the books. Stuff I used for class was on the right, stuff I brought from home was on the left.

Then, I started taking Judaic Studies courses. It was still easy to divide, because I was using all my “textbooks” for class. But now, I’ve completed several of the courses. I no longer need the books for class, but decided to keep them because they were interesting reads. So now, do these books make the leap over to the left side? Do they become seforim? Do ALL of them become seforim? If I move my JPS English-only Tanakh to the left side, do I also move “Jewish Philosophy in a Secular Age”? “The Bible Unearthed”? And where do Jewish history books fit in? Is it like the famous George Santayana quote, that if we do not learn from history, we are doomed to repeat it? Then what about the positive aspects of history? I can’t possibly recreate the enlightenment, though I view it as a positive period for the evolution of Judaism.

I think the broader question at play here is how should one treat the academic study of Judaism.

A few days ago, I was sitting in a gemara shiur (not a university class). We had been discussing a difficult mishnah, and in the gemara, Rav Huna and Rav Chisda tried to explain it various ways. Both of the explanations were a stretch, and it didn’t seem like either of them were “pshat”. So the rabbi leading the shiur showed us what Rabbi David Weiss Halavni, a professor of Talmud at

The Rabbi asked us what we thought about what Rabbi Halavni said. We all had to agree that it made a lot more sense, but a few students had reservations about his methods. “You can’t just disagree with the gemara like that. It’s not how we do things”, they said. So then The Rabbi said “What do you suggest for someone to do, if they’ve been struggling and struggling to find pshat in the Mishnah, and then they final figure out a way to understand it, but can’t find any amora who agrees with them? Should they just ignore this thought?” The student’s response: “Well, if they see a value in sharing their views, they shouldn’t publish it in a book that looks like a sefer.” [Rabbi Halavni’s book is written in Hebrew, leather bound, and is called ‘mekorot u’mesorot’]

I personally thought that what Rabbi Halavni said was great, and if I had a copy of his book, I would have placed it prominently on the left side.

I wonder where I would have placed his book 2 years ago, before I started learning secular Judaic studies?

Friday, April 13, 2007

Girls and Boys

Rabbi Kohl came to Maariv last night and showed us pictures of the baby. The boys asked him if the baby shared any of the Torah he had learned while in the womb with him.

The girls, all in unision, said "awwww" as soon as he showed us the picture.

Saturday, March 24, 2007

On Not Being Able to Spend Money. Ever.

I am a cheap Jew.

This may not surprise those of you who know me. You may have been frustrated with me when I got a glass of water when we went out for ice cream, or when I voted to rent a movie instead of drive to a theater, or when I buy off-brand groceries to save twenty cents. I apologize.

This is the way that I am, and I have [generally] learned to live with it.

I do very well on budgets. I feel like I have "won" if I am under budget.

I do not do well when I feel that money is being spent unnecessarily.

This is not a good character trait, especially when my roomate loves buying Bertolli pasta, Ben and Jerrys ice cream, Starbucks coffee, and Dannon yogurt. We started out buying groceries together. This did not last very long.

This is an even worse character trait when the money being spent is long term. Such as a student loan. Especially a loan that (I feel) is unnecessary.

I hate that my parents GIVE me money to spend on things like clothes, haircuts, and my car. They are not stingy at all, and many times tell me to get the top of the line (i.e. Get your car waxed twice a month, buy the fanciest clothes you can find for shabbos, spend the extra money to get the flight time that you want), yet also say that I will have to be the one to pay back my loans.

I don't WANT all these luxuries. I'd rather graduate debt free and not have a car. That's just not happening though. I "need" a car for when (2 or 3 times a semester) I drive to Baltimore. I "must" look nice l'kavod shabbos.

Last year, I was offered a full scholarship to Touro College, before I even applied. I thought about accepting it, briefly, but turned them down.

All things considered, I am MUCH happier here than I would be at Touro. It's not even a question in my mind.

I did, however, have a breakdown tonight about how much money I will have to pay back when I graduate, and I wasn't factoring in law school. It mad me think about Touro again.

I find my self repeating over and over "Beverly, you'd hate Touro. You would not learn anything there. Remember Darchei Binah? It's worse than that. Beverly, think about how happy you are at Maryland. Think, Beverly, Think!!"

Monday, March 19, 2007

L'hitaneg B'tanugim...L'Shadech HaBanot

"Reb Layzer made almost as much from the shadchen

(matchmaking) business as from his school, with the

added advantage that matchmaking was usually

accompanied by a glass of whiskey...This business was

conducted Sataurday evening between mincha and

maariv, when the Jews of those days, rested after their

twenty-four hour respite from work, were in the mood

to speak of such things."

Wednesday, March 14, 2007

May The Soul Be Lifted

Where does the idea of "an aliyah for the neshama" come from?

I've done some research, and the closest thing I've found is in the Medrash Tanchuma.

Rabbi Akiva was once walking, and saw a man with a faceI think this medrash provides much insight for mourners, both those that halacha specifies as mourners, and those that don't fit the halachick description, but are still are mourning the loss of their friend or relative.

"as black as coal", carrying a load "heavy enough for ten

men", and running "swift as a horse."

Rabbi Akiva asked him why he was doing this.

He responded "I am dead. When I was alive, I was a tax

collector.I exploited the poor and was easy on the rich. I

am punished everyday byhaving to collect wood for a fire

in which I am burned. "

Rabbi Akiva asked if there was anyway to free him from

this punishment.

The man responded "I have heard that if I had a son who

would go before the congregation and call out "Barchu es

HaShem Hamevorach", and the people would say "Baruch

HaShem Hamevorach leolam va'ed", and also, if he would

say "yisgadal v'yiskadash shmay raba" and the people

would respond "yehay shmay raba mevorach", then my

punishment would end.

He continued, "When I died, my wife was pregnant. But

even if it was a son, there would be no one to teach him."

Rabbi Akiva went to find the son. When he did, he found

that the boy had not even been circumcised. He

circumsiced the boy, and taught him Torah and how to pray.

When he was ready, he led the congregation in prayer,

including saying"barchu" and "yisgadal". When he did this,

the soul of his father was "instantly freed from punishment."

The key in the medrash was not that the son simply said the words "yiskadal vyiskadash...". It was the learning torah and teffilah part. Similarly, the father laments that he didn't get to "teach his son." If it was simply a matter of getting the son to say those few words, surely someone in the community (perhaps his mother?) would have urged him to do so.

The proclamation of "yiskadal vyiskadash" is so important because it speaks of elevating and praising God. The traditional reason given for this is because it helps the mourners realize that even though they are going through a difficult time right now, they still have to realize that everything God does to them is for the best.

The practical difference in this explanation, as opposed to the idea that kaddish "lifts the soul closer to God", is how it affects non-halachik mourners. When a person dies and leaves behind no one obligated to say kaddish, yet because of him people are doing more mitzvos than they would have, this is a zechus for the dead person. Praising God in public is a specific mitzvah one can do, but learning more torah or giving more tzedaka or being more careful about kashrus are comparable, in this case.

I've seen it happen where (usually non religous) families argue over who will take the responsibility of saying kaddish. Once one person volunteers, the others no longer feel obligated, because "at least the person has someone saying kaddish for him."

I've also seen it happen where people become disressed when someone dies without anyone to say kaddish.

Both of these situations bother me, because they are forgetting the point of kaddish. It is simply a way to help the MOURNERS deal with death. It's also not the act of kaddish that is important, it is the lifestyle that goes along with it. Why is it OK if only one son out of 2 or 3 feels enough of a connection to religon to say kaddish? Why doesn't the fact that none of the sons are shomrei mitzvot? And why isn't learning torah in zechus of a lost friend or distant relative not stressed more?

Religion and Personal Identity, Again.

That being said, I have another thing to say about it.

The friend I referred to has started becoming more religous. He's set up a chavrusa, he comes to minyan several times a week, and I see him at many of the shiurim that I go to.

I'd love to say that this makes me really happy, but it doesn't.

He's also stopped wearing his rugged baseball caps and put on a kippah. Instead of his grungy sweatshirts (or tee shirts, now that it's warm), he has started wearing polo shirts.

I see him slowly changing, exactly how my father changed. I'd love to say that I'm happy for him, but I'm not.

Since when is giving up your personal identity part of religion?

Monday, February 12, 2007

When Dad Goes Off and Gets Frum

I kind of have the reverse situation. My family, including myself, are all what one would call baalei teshuvah.

Growing up, my dad would repeatedly tell the story of when my mom was pregnant with me, their first child, he had a dream that 3 people-2 girls, one boy (presumably their 3 children)-were standing with him, and the youngest one, a girl in a nurse's uniform, said "Dad, being with you is like being in a time warp."

Disregarding the prophetic vision in this dream, focus on the last line. That's what growing up with my dad was like. I never knew what popular music was, our radio was always tuned to the "classics" like Kingston Trio, David Bromberg, and The Beatles. We listened to old radio shows like Dick Tracy and the original War of the Worlds instead of watching TV. When we did watch TV, it was Nick-at-Nite oldies like Route 66 and The Andy Griffith Show. My dad talked freely of growing up in the sixties and seventies, and sang us war protest songs from his youth. He tried to hide the fact that he smoked and took all sorts of drugs, but once it came out, he was pretty open about that too. When I went to Amsterdam this past winter break, he told me, only somewhat jokingly, that I should get high while I had the chance. I used to look forward to our big Friday night dinners, where the conversation ran freely and anything and everything was always discussed.

Then, slowly, my family began flipping out. I guess in a large way it was due to me-I stopped wearing pants in 4th grade, and my mom followed. I started only eating vegetarian when we went out to eat, and my dad followed. Then, I wouldn't eat out at all, and since my family had to cook something else for me, they stopped eating out so much as well. I went to a high school out of state, because there were no Jewish high schools near where I lived. When I started there in 9th grade, my family was probably one of the least religous families. We still would eat dairy in non kosher restraunts, my mom didn't cover her hair all the time, I didn't even know what mincha was. The girls in the school, for the most part, came from relatively shtark families. The school defined themselves as a "non-Bais Yaakov." Now, just a few years later, my parents would probably not have sent me to that school, as it's too modern for them. My dad wears a black hat, and has a beard and peyos. Not that I judge people by what they look like, but...I do.

Friday night, I've noticed, isn't the same unless my dad has had several shots of whiskey. If not, then it goes like this. He and my brother come home from shul, and sit down on the couch to rest for a few minutes from the 20 minute walk home. The women, who have been home the whole time and haven't eaten properly the whole day because they've been busy getting ready, are extremely hungry and want to start kiddush ASAP. Finally, we get the boys up and to the table, and everyone starts singing Shalom Aleichem off-key. There's always an argument whether or not to sing Eishes Chayil, as my parents don't really know the tune or the words, and so its up to us kids. None of us have great voices, and while this doesn't bother my brother or sister, it bothers me, especially if there are guests. Kiddush, Hamotzei, Fish, Soup and then the fun begins.

My father gives over a dvar torah. He's worked really hard at preparing this with a Rabbi that he learns with, so everyone is very quiet while he speaks. It's something that usually takes him about 5-7 minutes, quotes a rashi, and has a "feel good" mussar point at the end. You can't question him, because he just hasn't learned enough to answer analytical style questions. If our non-religous relatives are there, it gets even worse, because some sort of arguement always ensues about "The Rabbi" that always gets the final say, or women's role, or our relationship with non-Jews. I'm always quiet during these things, but I really don't think my father presents Orthodoxy in the best light.

What bothers me so much is not the lifestyle my father has chosen. When I was in Seminary, I was surrounded by people like him. I didn't really mind them so much, because that's just how they are. What bothers me is that I remember what my dad was like just a few years ago. His Orthodoxy has made him lose so much of his personality. Now, everytime I go home, he's more interested in learning with me than with speaking with me. I can still get him to be like how he used to be, but usually only when he's had a couple of drinks, or times like lazy Sunday mornings when he sleeps in and doesn't go to shul, and therefore isn't in the "shtark-mode" so much.

I have a friend who lives about 4 hours away from my hometown and reminds me SO MUCH of my dad (pre-flipout). I really want to introduce my dad to him, but right now, I don't think they'd get along very well. If I had met him 3 or 4 years ago, things would have been different, but now, my dad would immediately have a negative reaction to him when he sees him not wearing a kippah, but a cap with the Beatles logo on it. And my friend would think that my dad looks like an old Hasidic rabbi. And then they'd talk Torah. And they maybe wouldn't hate each other, but they would each think that the other one is a little bit crazy. And they would probably never get around to discussing things that they have in common, like music. My dad would try to show off how shtark he was by saying that he listens to the Miami Boys Choir. I know my dad secretly despises them, but it's the frum thing to do. He can't listen to goyishe music anymore, so instead he listens to the Big Band music of the 40s. And this breaks my heart.

I've recently started going to minyan everyday as well, and I love it. I love the camraderie and the "minyan chevra", and I also love that it sort of forces me talk to God 2 or 3 times a day. I would never want to suggest that my father not go to minyan, or not learn daf yomi, or spend less time with the kollel. But at the same time, I really miss the old him. I miss taking weekend camping trips to middle-of-nowheresville South Carolina. But we would never do that now. Its too much time spent away from the shul. And I've come to really resent that.

Monday, February 05, 2007

Don't Worry, Be Happy

A friend of mine came by my room, and we were discussing the posters (I'm not a fan).

She pointed to one of the posters

and said "You know, he's not so bad looking." I made an "are you crazy?" face, and told her that if I were to choose, I would go with the other one:

She said "Really? But the first one is so...pensive."

She said "Really? But the first one is so...pensive."

"True," I responded. "But the other guy looks so happy and carefree."

And that's the difference between her and I.

Tuesday, January 30, 2007

Proud To Follow Halacha

Last year, I was in an environment where part of the dresscode was that girls were required to cover their legs, either with a long skirt, or the more popular option, with tights. The head of the school's wife taught a class on tznius, and this issue came up alot. The class was based around the book Hatznea Lechet, by Rabbi Getsel Ellinson. After going through the sources, it was clear that one is in no way obligated to cover the bottom part of the leg, unless one defines that as the shok, in which case the skirt would have to go all the way to the ankles. There is some discussion of minhag hamakom, and many people say that when one enters into a place where it is customary for women to wear tights, one must respect the people of the place and wear tights. My school was of the opinion held by Rav Elyashiv, that the minhag Yerushalyim was for girls to cover their legs.

So the obvious next question to this seminary leader was "what do we do when we get back to America?" In most communities in America, there is no clear minhag of all girls wearing tights. Her answer was "Look at the women you want to emulate. Even in these communities in America, the vast majority of them cover their legs. It's not a minhag hamakom,per se, but its more like a minhag kedoshim." (I thought about this and realized I don't know any women that I would really like to emulate, period. I can think of a few men, and I highly doubt that they would wear tights year-round. But who knows. Maybe they would. Or maybe they're just not kedoshim.) She told us that in no way can she tell us we must cover our legs. But she just can't tell us NOT to, either.

Well, I don't. And I don't feel like I'm not a kadosh person for it, either. (Maybe for other reasons, but certainly not because of my lack of tights.) But, thats not really the issue here. The issue that I've been grappling with is, why do religous women wear skirts? There are three answers traditionally given for this question:

1. The Torah prohibits men wearing womens garments and women wearing mens. Pants are considered clothing of men.

2. The pants show the outline of the leg.

3. The pants show the split between the legs.

Out of the three, only the third is, in my opinion, somewhat valid. Black sweatpants with pink lettering are certainly not anything a man would wear. If the pants are loose enough, you can not actually see the outline. So loose, feminine pants should be OK, if not for number three.

However, I have a problem with both the second and third reasons. Where in the world do they come from? Is it just a general prohibition, like not wearing tight clothing, that violates the "essence" of tznius, without violating any actual halachos? I don't know, I see plenty of girls walking around in very nice, professional pants that do not look especially immodest. So I turned to my guide, Hatznea Lechet, and I found the followings answers:

Avnei Tzedek responds to a question about women wearing pants under their skirts "Surely, pants under a girl's clothing, or even on top of them, are permissible, since the woman will ultimately be recognized as such by her other clothing, and since she is only wearing this garment as protection from the cold."

He obvioulsly is of the opinion that pants are neither beged ish, or promiscuos. If so, he would have outright prohibited them. The like "even on top of them" leads one to believe that he feels that in certain instances, it is OK for girls to wear pants in public, although he does not seem to be advising this on a constant basis.

The Yaskil Avdi (who, I must admit, I have never heard of) writes that women's pants are certainly not k'li gever, but "should be forbidden for a different reason. Pants are immodest clothes for women, since the legs are seperated to the top. Someone who sees a girl wearing pants may be led to bad thoughts..."

I don't have a copy of the yaskil avdi, so I could not read this inside. No sources (of the yaskil avdi) were quoted in Hatznea Lechet (sometimes sources are quoted.) I don't know where he gets the idea that all pants lead to immoral ideas. They just don't. He seems to be referring to specifically the pants that are cut to fit in a certain way, and this would fall into the general prohibiton of not wearing tight clothing because it arouses attention. I was reading this and thinking, it's really not so bad to wear loose sweatpants. It would be so much more conveniant for rolling out of bed and going to class, and not wearing pants is not spelled out expicitly in halacha. (hehe, maybe my friends in israel were right...)

Then I read Rabbi Ellinson's footnote. He wrote that

"Another factor which must be taken into account is the existence of a

community of modest Jewish girls with their own standard. The fact that they

are careful to wear only skirts, affords signifigant weight to this

stricture. By wearing a skirt, a Jewish girl identifies with this group and

seperates herself from other more permissive circles.

To a certain

extent, in the last few decades the skirt has become a sort of Yarmulke for the

scrupulously observant girl who strives to follow our sages ethical guidelines,

as reflected in their halachic rulings. By her refusal to wear trousers, she

demonstrably declares that she is unwilling to resign herself to the dictates of

modern style, and that she takes exception to the immorality so rampant these

days in society at large."

He then quotes his daughter as once saying:

"Even if it could be proved beyond the shadow of a doubt that there is nothing

wrong with wearing trousers, I would still continue to avoid them."

I though about the Orthodox people that I know that wear pants, and I realized he is right. I can think of one or two people I know that wear pants and that I respect as being very commited to torah and mitvah observance. But as a whole, there is this category of "people who are Orthodox but wear pants." These are generally the same people who look forward to shabbos because of the "onegs" after dinner and don't really care so much about being shomer negiah.

Then I though about what my seminary teacher had said about tights. For a minute there, I condsidered digging out my old knee socks. It seemed like exactly the same idea. But it's not. Only because, for some reason, wearing skirts has become a UNIVERSAL sign of religiosity, where as wearing tights is only a universal sign of chareidism.

When I first got to college, I mentioned to a friend that if I was a guy, I would definately want to wear a yarmulke here, as opposed to a cap. It's so nice and refreshing to see guys walk around stateing clearly "I'm proud to be Jewish." I think that wearing a skirt is the girl's equivalent. It's not just a mere following of halacha, but a sign that says I am proud to follow halacha. And I am.

p.s. This post definately accomplished it's purpose as stated in the first 2 lines. And the conclusion is in the title.

Sunday, January 28, 2007

Seminary at UMD

Thursday, January 18, 2007

Free Advice

The following comments were each said by different people, at different times:

* "You should speak to Rabbis about your classes" (she was referring to my Judaic Studies classes)

* "You should read more mussar sforim"

* "You should speak with ______, she's an EXCELLENT psychologist"

*"How's your emunas chachamim?" (This was asked by a teacher that I was pretty close to last year, and I wrote a paper in which the conclusion of the paper was that emunas chachamim is a concept made up by the rabbis in order for them to maintain their authority, and today's version of emunas chachamim is actually the opposite of what God intended when He wrote "lo tasur min haDavar yamin u'smol." I couldn't actually hand in that paper to the head of the school, who was grading them, but this particular teacher was the one who helped me edit it, and told me what I could hand in and what I couldn't. Maybe I'll post that original paper one of these days.)

*After telling a friend who stayed shana bet that I'm not sure I want to make aaliyah anymore, she said "OH no. That's it. America is too dangerous. I'm filling out the Nefesh B'Nefesh papers tomorrow. I wasn't sure if I should do it this year or next, but this just proves that I need to do it NOW!"

I wanted to scream at them "I'M FINE. Really. Don't worry-I'm not planning on going off the derech anytime soon." It's weird, because they all know me pretty well. All I could think of on the plane home was "Are they right?"

UPDATED TO ADD: A friend wanted to set me up with a guy who is theologically Conservative. I am truly baffled by this.

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

Proper American Speech

Sunday, December 03, 2006

What's Love Got To Do With It?

(שמואל א א׃יח)

OK, this post is not going to talk about the implications of this posuk for the Gay/Lesbian community. Maybe I will discuss this in another post. When discussing this posuk with my chavrusa, we got into a discussion about what the Torah means by "ahava", or "love".

I decided that an interesting project would be to look at how "ahava" is used in various places in tanach, and see if I could draw a conclusion. What I found is really interesting.

There is a concept when learning tanach that if one wants to know what a word means, they should look to the first place that the root is used, and use that context as a guide.

The first place that the root א.ה.ב is used is Bereishis 22:2 :

וַיֹּאמֶר קַח-נָא אֶת-בִּנְךָ אֶת-יְחִידְךָ אֲשֶׁר-אָהַבְתָּ, אֶת-יִצְחָק, וְלֶךְ-לְךָ, אֶל-אֶרֶץ הַמֹּרִיָּה; וְהַעֲלֵהוּ שָׁם, לְעֹלָה, עַל אַחַד הֶהָרִים, אֲשֶׁר אֹמַר אֵלֶיךָ

"And He (God) said, 'Please take your son, your special one, THAT YOU LOVE, Yitzhak, and go for you to the land of the Mountain Moriah, and bring him up their as an oleh offering on one of the mountains which I will tell to you."

In the begining of this posuk, God is instructing Avram to bring his son as a sacrifice. Avram is confused, because he has two sons, and doesn't know which son God wants him to take. So God tells Avram to take his "special" son. But Avram's a good father, both of his sons are special to him. Then, God says "the son which you love" and it is this phrase that seperates Yitzhak from Yishmael.

The Torah is making pointing out that there is a distinction between that thinking of someone as "special" and actually loving them. In today's world, when we talk about "our special someone" we are referring to the one person we love more than anyone else. But, apparently, our view of love is not the same as the Torah's. Love is something more than just viewing someone as really special.

Besides for familial love, there is one other context in which the Torah talks about love. That is in the mitzvah of ahavas HaShem. The mitzvah is found in sefer Devarim 10:12

וְעַתָּה, יִשְׂרָאֵל--מָה יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ, שֹׁאֵל מֵעִמָּךְ: כִּי אִם-לְיִרְאָה אֶת-יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ לָלֶכֶת בְּכָל-דְּרָכָיו, וּלְאַהֲבָה אֹתוֹ, וְלַעֲבֹד אֶת-יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ, בְּכָל-לְבָבְךָ וּבְכָל-נַפְשֶׁךָ

Note that here, when the Torah tells us to love God, the phrase used is וּלְאַהֲבָה אֹתוֹ.

אַהֲבָה is a noun-love, as the thing love. But then what does וּלְאַהֲבָה mean? Technically, its, "And to love(noun) Him."

This is confusing. We see from sefer koheles that there is actually a verb-infinitive of ahava:

עֵת לֶאֱהֹב וְעֵת לִשְׂנֹא

(Koheles 3:8)

Why can't the Torah also use the word לֶאֱהֹב? Obviously, God wants to teach us about what real love is, and what it is not. Love is not simply having much affection for something. When we say "I love chocolate brownies" we are not actually using love in the right way. There's no doubt that Yaakov had ALOT of affection towards Yishmael. In todays terms, it would be called love. Yaakov loved Yishmael dearly. But, not according to the Torah.

So what can the Torah mean by "love"?

The answer, I believe, can be found in last weeks parsha, when the word ahava is used once again:

וַיַּעֲבֹד יַעֲקֹב בְּרָחֵל, שֶׁבַע שָׁנִים; וַיִּהְיוּ בְעֵינָיו כְּיָמִים אֲחָדִים, בְּאַהֲבָתוֹ אֹתָהּ

"And Yaakov worked for (or "with") Rachel seven years, and they were in his eyes like a few days, in his love(noun) for her"

Yaakov's whole focus, while in the house of Lavan, was Rachel. He worked seven whole years just to be able to marry her. Everyday when Yaakov went out to work, he knew the only reason he was doing it was for Rachel. He put up with Lavan for 14 years just to be able to marry Rachel. Yaakov's whole life's focus at the point was Rachel. Yaakov was "in love" with Rachel because everything he did, he did for her.

This is what I think the Torah is telling us love is. Love, true love, is when your whole life's focus is the object of your love. Thats why Ahavas Hashem is a noun. It's not a simple action. One can not just bring a korban and say, "OK, now I've fulfilled the mitzvah of ahavas Hashem" and then check it off his list. It doesn't work like that. To love God means your whole life is dedicated to God. Everything that one does, they do for God.

This is what distinguished Avram's relationship with Yishmael and Yitzhak. Sure, Avram adored Yishmael. He had alot of affection for him. It's only natural-Yishmael IS his SON, afterall. But the difference is posterity. Deep down, Avram knows that eventually, Yitzhak is going to be the one to continue the family legacy. Avram, as much as he may "love" Yishmael, knows that his life's work of spreading the idea of Torah Monotheism will be continued not by Yishmael, but by Yitzhak, the son that he loves.

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Ignorance is creativity...a reflection

I just spent the past 6 hours studying for a math test with another dear friend, "Danny". Danny is somewhat of an atheist (he's a little confused as to what he believes at this point), but more importantly, he's a philosopher. He's only 19 years old, yet he is brilliant beyond his years. Danny and I have the craziest conversations, that only someone as insane as I would understand, much less enjoy. Whats unique about Danny is that when I say something outlandish, instead of nipping it in the bud and explaining why it can't be, Danny will proceed to expound on it, and develop the idea as if it was something that could and should happen.

For example, once I mentioned that someone I know was told as a child that God only gives people a certain amount of words, and once you use up those words, you won't be able to speak anymore. Other people that I've told this too responded in one of two ways: 1. They said that it's probably just illustrating how important it is for one to think about the necessity of their wordsds before they speak, or, 2. They try to convince me that this is impossible since God wants you to do certain mitzvot, like teffilla, that involve talking, every day of your life. Danny, on the other hand, just expounded on that and went on to discuss how much different our lives would be if we had to ration out our words, and asked if this would apply to the written word as well?

Danny thinks so much out of the box that I don't even think he realizes there is a box. He hasn't yet got to the level of comfort with the way of the world to become sedated in his musings. His thoughts are absolutely insane, but at the same time, insanely rational. I could sit and talk to him for hours about absolutely nothing, and at the same time, feel like a smarter, more intellectual woman.

What I wouldn't give to see his thoughts for a day...

Monday, October 30, 2006

Part II-"Friday Afternoon"

"So did you call the health center, and poison control center?" I asked.

She said she did. The Poison control center told her the toxic level of contact solution is very low, so not to worry about that.

The health center told her to try various methods of getting the contact out, such as:

*eating something hot

*eating bread

*going to the bathroom

*throwing up

When none of these methods worked (Ok, she didn't try the last one) she called the health center again, and they told her to go to the ER. So, 2:30 Friday afternoon, 3 and a half hours before Shabbat, we head out to the Hospital.

Eliana has since come up with a theory about hospitals. "The whole point is to simply move you from waiting room to waiting room, so that you think they are getting something accomplished."

When it was 5:00 and we had only been seen by the triage nurse, it was pretty clear we weren't getting out of there before Shabbat. We called the campus rabbis, and one of them offered to walk the 5 miles to the hospital to come and meet us after dinner! We told him no way, we did NOT want him to walk ten miles in the cold rain for us.

The other one advised taking a taxi. It's better that a Jew not do the driving, and theres no way we could have walked. Theres more to this psak than simply that, but I don't have time to go into it now. Perhaps a later post.

We still weren't a hundred percent sure what we were going to do when we finally were ready, but as the sun set, Eliana and I sang lecha dodi to the passing police officers, men in handcuffs, and drug dogs.

Part I - "Friday Morning"

"All right," she thinks to herself. "I'll be healthy and take a calcium pill today."

She reaches for the pills and then realizes that since she doesn't usually take pills in the morning, she doesn't have a cup in the bathroom. But, no worry, her roomate's cup in sitting convienently on the counter. And even more conveiniant, there's already water in the cup.

"Sweet!" Eliana thinks to herself as she gulps down her pill with the water.

But as she drinks the water, "sweet" is not the term coming to mind. More like "bitter" "burn" and "acid". Thinking that it must not have been water she swallowed, she asks her roomate what was in the cup in the bathroom. Roomate responds "My contacts and contact solution. Why?"

"Eh.." Eliana responds. "I think I just drank your contacts!"

Saturday, October 28, 2006

Math and Rav Kook

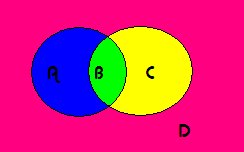

So, in math, we're learning about complements. The complement of a given set is anything that's not part of that set. This is the venn diagram which illustrates what the complement is:

In the diagram, the left circle represents everything in group A. Everything not in group A can be defined in three ways. First, you can simply call it "C and D", or you could call it "A complement." The way to write "A-complement" is Ac.

This gets more interesting when you start to assign actual values to the letters. For example, you could say that A represents all the people who ate at Hillel friday night , and C represents all the people who came to shul Friday Night. B would be the people who came to shul AND ate at Hillel, while D would be the people who neither came to shul nor came to eat at Hillel. Ac would be anyone who did not eat at Hillel, regardless of whether or not they went to shul on Friday night .

I find this interesting because when writing down math problems, my professor tends not to write the symbol Ac, opting instead to write a different variable which describes this group, perhaps S for "starved" (in this example, it doesn't quite work because obvously people who didn't eat at Hillel would have eaten somewhere else and would not have starved, but you get the point)

I thought about this today while learning a letter of Rav Kook. In it, he discussed the idea of a culture and a counter-culture. The hippies of the 60's were a counter-culture, a response to the general straight and narrow culture of the time. He talked about non-religous Judaism, and whether chiloni society is a culture or a counter-culture. In other words, do you define non-religous Jews simply as "NON RELIGOUS Jews" or are they something more than that? Are they "my neighbor down the block with the really pretty flower garden " and "That really funny guy in my Biology class", or are they simply "The group of people who are not religous.

Rav Kooks point is that its so easy for religous people to look at the rest of the world and think of them as "Religous-complement" but thats an entirely wrong way of looking at things. A guy I know, "Bobby" is possibly the most insightful person I've ever met. And I happen to know alot of really insightful people. I really value Bobby's opinions on almost everything. It doesn't matter to me that Bobby is not particularly religous-I can still count on him to explain my math work to me, or to shed light on a really complicated sugiyah I'm learning.

So often, we as religous Jews fall into the trap of staying in our own little Jewish circle, and never really branching out beyond that. A friend of mine grew up in an ultra-Orthodox family, went to Ultra-Orthodox schools her whole life, attended an Orthodox seminary in Israel, now is in Yeshivah University, and is getting married soon and moving some Chareidi nighborhood in New York. I'm not judging her particular choices, for her they probably were the best move. However, this girl does not have any real exposure to people who are not exactly like her. And that, in my opinion, is really dangerous. I mean, she could live her whole life never having to really think about why she is religous. And worse, she won't be able to convey that over to her children if she herself is unsure. And then people wonder about the "crisis" of kids going "off the derech." Amazing.

Sunday, October 15, 2006

Shake your...checkbook

How true.

You kindof have to wonder what the rationale behind it is. Ok, we do it cuz God said so, but...why? It seems to me that succot comes in the fall. Ok, wait that didn't come out right. It's obvious that succot comes in the fall. It seems that the time of year is vitally signifigant to the underlying reason behind the mitzvah. Fall is the time of harvest. Many other cultures have harvest festials. In essense, succot is the time that we look at our produce and realize that it's all from God. We have to take a moment from our excitement and thank God for allowing our crops to grow.

Untill recently, almost every society was highly dependant on agriculture. Most people either grew their own crops, or grew cash crops to sell, enabling them to buy other types of food to feed their families with. If the crops didn't grow one year, you didn't eat.

Nowadays, we have a somewhat different culture. We're still dependant on agriculture, but not to the same extent. If florida has a bad year of Oranges, we can order from California instead. We may see tomatoes rise in price to over $3.00/pd., but we would never starve to death because of it. Thank God.

Today, we are much more dependant on business. I personally know day traders who committed suicide because the stock market went down that day. Our society is an economically minded one. We no longer care about the dividends of the field, rather, our interest is the dividends of the checkbook. With this in mind, maybe we can change the way we view sukkot.

Instead of thinking how silly it is that we are standing outside waving around a bunch of plants, we should imagine we are waving around our wallets, or laptop computers.

Succot is, in essence, a holiday of thanksgiving. Its the time where we look to God and say "Everything we have comes from you. Without Your graciousness, I wouldn't have my cozy warm bed, or even my house. I wouldn't have any food to eat, or money to buy food with. Thank You God, for providing me with sustenance."

*It bothers me when people refer to the 4 species as "lulav and etrog". What did the haddasim and aravot do that they don't deserve to be included as well?

If Mastercard celebrated Succot

Construction paper to make paper chains and other decorations......$3.69

Holiday meals at the UMD Hillel......$45.00

Sleeping under the stars.....Priceless